Who Will Sleep? A Night Festival in Uttarakhand with Fire Swinging and Walking on Blades

A young student and adventurer from Uttarakhand’s Garhwal region introduces the revelry and history of Selku (meaning: who will sleep?) – a local festival celebrated with fireplay and a walk in trance on holy blades.

Story by: Divya Nautiyal

I still remember myself as four years old, inside the kitchen, wearing my new red sweater and waiting for lunch, when the beat of drums surprised me. Confused by the sudden surge of energy among my family members, I trotted behind my mother outside. All the women in my family were standing in the balcony with their hands folded in pranam, their gaze fixed on the source of the drum beating and the excitement apparent on their faces as they anticipated the dancing in the festival. 17 years later, wearing my favorite dress, I am dancing to the same beats with my friends and family, celebrating the fair of Selku in my village Mukhwa in the Garhwal region of Uttarakhand.

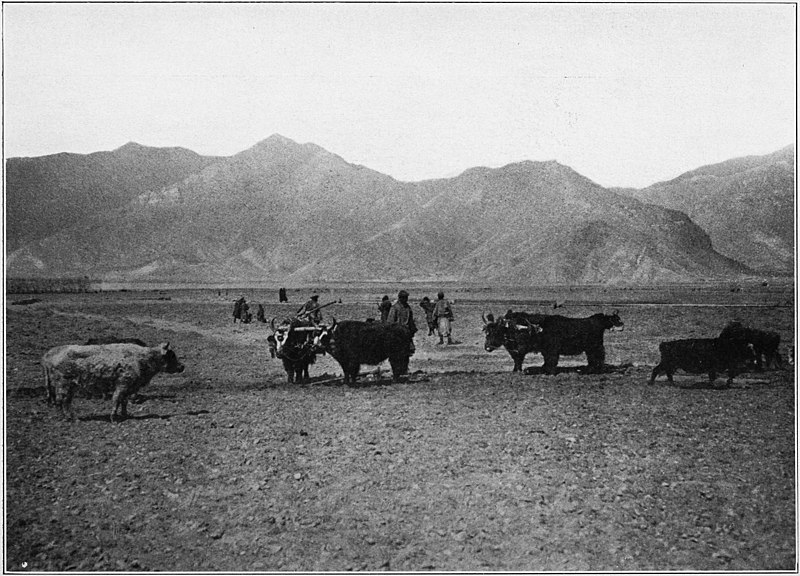

The festival of Selku has a long and interesting history. ‘Until the victory is won, we have to strive,’ was the slogan of the Tibetan salt collectors in ancient times. Located at an altitude of 11,000-13,000 meters above sea level, the black barren soil of Tibet had little capacity for food production. The Tibetans thrived in their nomadic life, shepherding their yaks, sheep and goats. Men of the community would journey away from their families to the lakes formed on the plateau to collect salt. These men identified themselves as the ‘saltmen’ and spoke the salt language (I couldn’t find a name for the language though, and I don’t have an idea whether it is still spoken). They travelled on foot for months with their yaks, fighting the dry winds, scorching cold and hunger pangs, to reach these salt mines – and returned home with yaks laden with grainy salt.

Mukhwa – where I was born – is a village nestled on the high banks of River Bhagirathi, about 20 kilometers from Gangotri. Today a well established and populated village, it housed only 13 families once. The residents worked hard in their fields to grow barley, rajma (kidney beans), potatoes, peas and other grains and cereals. As its population grew, so did its inter-border trade. Located close to the Tibet border, for centuries the buderas (local name for the residents of Mukhwa) traded with people living on the other side of the Himalaya.

Traversing the great mountains, rugged terrain and harsh weather conditions, a representative from each region would meet and make an agreement by breaking a piece of stone into two. Each representative would keep a piece which served as a way to endorse the agreement. On the day of the actual exchange of commodities, the Tibetan trader would match the broken piece with the one owned by the trader from Mukhwa. For every kilogram of salt, 4 kg of grains was exchanged between the traders. Other than coarse grains, yarn, precious and semi-precious stones, herbs, spices, tea, dry fruits and shawls were bartered too.

The inter-border relations were not always smooth though. I’ve grown up hearing stories of raids, kings and their hidden treasures. Even though the traders and village folk developed strong bonds, the Tibetans often raided the neighboring border villages of Jadung, Nelang andMukhwa. The reminders of these raids are still seen today in the form of myths of hidden treasure and discoveries of odd, buried items such as glassware, spoons and other items in the fields of Mukhwa. Over the years, farmers in Mukhwa have found coins, spoons and buried bricks in their fields!

Finally, in 1962, the war between India and China cast dark clouds upon the inter-border trade. Men from Mukhwa joined the war and aided the Indian army in their fight against the Chinese. I met an old man from Jadung who remembered, quite vividly, the aftermath of the war in Mukhwa and Bagori. He described how the Indian army blindfolded innocent Tibetans and led them safely across the border into India, where they found refuge along with their cattle. After 1962 however, all border routes are heavily guarded by the ITBP.

From the elders, I’ve heard that during the war, every single day, mothers and daughters offered prayers to Lord Someshwar – the local deity of Mukhwa – hoping against all hope for the safe return of their sons and husbands. Neither word of mouth nor letters could travel from the war zone to the people left behind. No shade of azure sky or change of season brought comfort to their frightened hearts. With sleep-deprived eyes on the desolate road, and ears yearning to hear the sound of victory, the unspoken agony of war was tormenting. With each passing day, the hope of even the strongest was fading.

I imagine that every soul in Mukhwa was huddled in blankets on their charpais (woven beds), with the freezing cold and the fear of black bears, when a distant sound alarmed them. The sound continued to grow louder and in no time, everyone was out of their houses. Victory horns were being blown and war songs sung. The battle had been settled (as there were negotiations and agreements made between the two countries) and the men were returning safely home. Everybody danced and ate and drank their hearts out. It is said that nobody slept the entire night but celebrated and made merry – and hence started the fair of Selku, rooted in the Garhwali phrase Selu-ku, meaning “who will sleep?”

The main feature of Selku is the fireplay at night and Someshwar’s walk on holy blades the next day. The whole village brims with vigor and enthusiasm as it prepares for Selku. Strong young men set out in search of the wild flower Brahmakamal (scientific name: Saussurea obvallata), which grows at an altitude of 4500 meter, bringing back ringal (bamboo) baskets full of Brahmakamal and other flowers like Himalayan geraniums, musk larkspur and Govan’s corydalis. The women spend the day collecting flowers and herbs in our small baskets from our gardens as offerings and decorations for Selku. The flower of Brahmakamal is considered a holy offering to the gods and goddesses. The energy of the tired flower collectors is revived with one of my favourite Selku delicacies, dyuda. It is made of cornflour and jaggery, and served with ghee and jholi – a spicy curry preparation with mashed potato as its main ingredient.

Ringal baskets filled with Brahmakamal and M. larkspur, brought back from the meadows in Mukhwa. Photo: Divyanshu Semwal

Govan’s corydalis. Photo: Divyanshu Semwal

The fireplay begins at night. Chips of deodar wood are tied with a metal wire, lit on fire and swung by the men. Everybody dances to the beat of the drums and performs Rasu, the Garhwali folkdance, around a big fire. The next day is marked with the worship ceremony of Lord Someshwar. The village priest makes an offering to Someshwar and prays for good health, better crops and happy lives of the people.

Following the pooja (prayers), the palanquin of Someshwar appears, carrying a person in trance, who performs Aasan— the walk on holy blades. Someshwar chooses the person. Men hold the holy blades, one in front of the other in a line, and the person in trance walks on it supported by other men on two sides! It is believed that before going to war, Someshwar prophesied of victory – and he performs this walk to bless people and be part of the celebration. Each happy heart joins hands to perform Rasu together to the beat of the drums. Selku is also a time for daughters who’ve been married in faraway lands to re-visit their village. The air is filled with happy laughter, celebration and remembrance of the valiant hearts who fought for us.

Older than the memory of the oldest person in Mukhwa is the tale of Someshwar’s long, arduous journey to find peace and a place to call home – a story that is known to every generation in Mukhwa. Someshwar started to move from Kullu, through the Himalayas, and arrived in Kashmir. He kept moving upstream. Traversing through fertile lands and desolate villages, he emerged in Jakhol in Uttarakhand, under a Himalayan cherry prinsepia tree. After blessing the Netwaris (people of the region), he left Jakhol and reached the pine jungles of Kharsali, Yamunotri. Wherever he stopped, he established his abodes along the way but still no place gave him peace. Moving higher up towards the source of the Ganga, he arrived in Raithal – a village filled with chestnut trees – where he was embraced with love. His calling further led him into the Bhagirathi valley to Sukhi and finally to Mukhwa, where he is said to reside till today.

When the Tibetans raided Mukhwa,the people were not able to defend themselves. Every attempt to fend off the Tibetan raiders and goons was met with failure. However, it is believed that before going to war in 1962, Someshwar prophesied of victory and blessed the men going to war. The miracles and prophesies performed by Someshwar earned him the respect of a higher deity. Hailed as the king of the higher Himalaya, his blessings bring rain to the crops, victory to the defeated, healing to the sick and solace to the wanderer. People from all over the region come seeking his blessings. It is believed that Someshwar arrived in Mukhwa on sankranti of ashwin i.e. the first day of the month of September according to the Hindu calendar. Although the war took place in October, Selku is celebrated in September too – but there seems to be a gap in history as to why.

In a time when India was under the British tyranny, a little hamlet made up of only 13 houses, managed to preserve its culture and beliefs and passed to the generations. So as I take part in these festivities today and witness the roots of my culture, I’m left awestruck, inspired and happy. Every little note of a folk song, beat of a drum, cheers of the people takes my heart down the lane time when life was not easy but nevertheless people persisted and wrote history.

Meet the storyteller